Commentary by the Editor

Juarez, Chih., Mex. — So how did this Cartel War begin and how does it end?

The Border Blog will not answer that today. We look for the things that make the heart tick and leave the fancy thinking to those that make these messes in the first place.

Roughly, for me, it began a long time ago, when the people who have most of the marbles understood that they didn’t have to do a thing about bringing along another class of people who had hardly any marbles at all. Impunity. No apologies. In Juarez the maquila industry began when someone figured out that Labor was a cheap product that Mexico had a lot of and that it could be exchanged for some major profit. Of course nothing so crass as that was said. Rather, this was the bright new day that would lead to a burgeoning “middle class,” and bring everyone up from the bottom. So they said. So the “development” of Juarez began. The powers that be brought willing companies looking for labor and they delivered “labor.” This labor, also known as the citizens of Mexico came from the far flung corners of Mexico. They had nothing else to do and would work at any price, went the theory. Everyone would be happy. You move here, we’ll give you subsistence (and societal dislocation), and we’ll go to the bank. Everyone will be happy.

Right?

When I first started photographing in the maquila factories of Juarez in the early 1980’s the salary in a maquila was $5 per day. Today it’s a little over $7. A full two dollar increase in 20 years. Imagine!

It wasn’t sustainable then and it isn’t now.

The promise of some kind of job, of rising above downright depraved poverty, was strong and people flocked to the border factories. First from Veracruz, then from Durango, then from Torreon and on and on.

If you were a Mexicano and wanted to improve your life without the terrible alternative of actually crossing the border and trying to make it work in El Norte, you headed to the maquilas of Juarez or Tijuana or Nuevo Laredo. If you made that journey you left your culture and customs behind. This was the brave new world.

Bienvenidos campesinos.

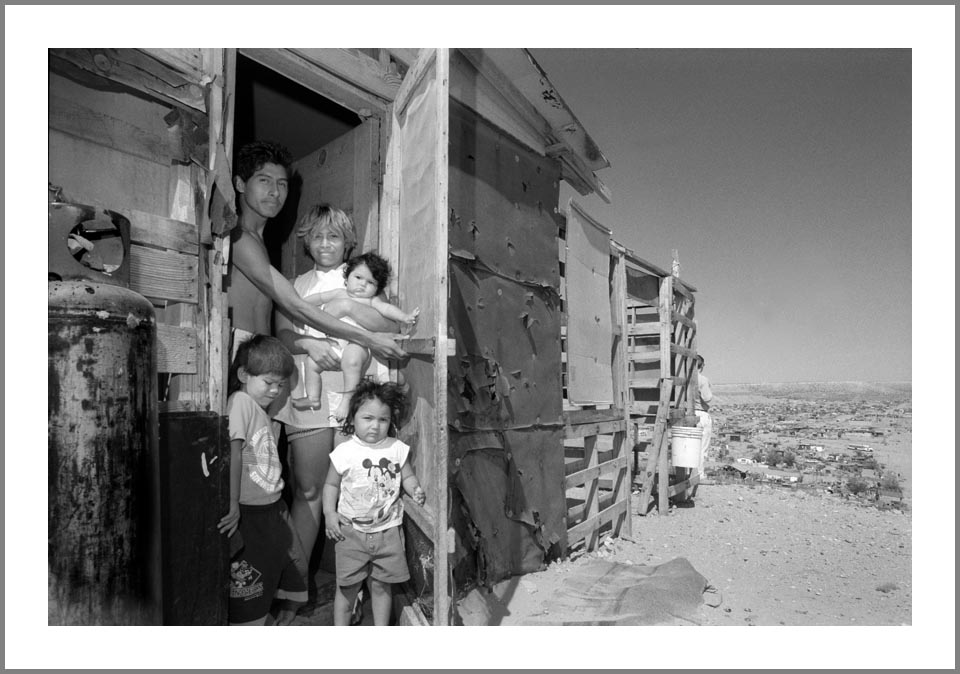

The familia Hernandez came. They made the trek from Torreon when they were just kids. They had no money and no connections. He found a place to squat and built the family a small house, looking out over the river, across to the Americano university that sat on a hill overlooking the ditch of the Rio Bravo. He got a job in a maquila. Actually, several, one after another. He improvised truck pallets and made a house. They paid for water, every few days, from a water tanker truck. The water wasn’t clean but they boiled it. They pirated electricity and when the Juarez utility cops yanked it out they did without it. They struggled to make it. Their families were long gone behind them. They couldn’t afford to go back and visit. At $25 a week and with three children and one on the way, they used their money to eat and survive. Stuck in Juarez. Detached from the past. Afraid to raise their heads and look forward to the dream they had come here to live, they succumbed, and they became the new Mexico.

This family portrait was made in the mid nineties, a generation ago.

The oldest child in this photograph is now old enough to work, and have a family of his own. There has been less work in the maquilas than there was in the “hay day.” Things happened. The world economy went down. The violencia came. Things got tougher. There is significantly less employment in the small business economy of Juarez because an enormous amount of small businesses have packed it in and closed or, crossed the border and started again in a new form, or headed to the Capitol (and other parts south) to see if they can stay in the country and continue on, hoping for a better day. Additionally, since the PAN party has been in power for the past 12 years there has been less federal money filtering into ciudad Juarez, less money floating around.

Upheaval has destroyed the economy of Juarez.

So how do the people live and possibly prosper in an economy built on the foundation of living off of the industrial power of the first world? A one trick economy designed to deliver profit and hope that somehow, if nothing goes wrong, it’ll fix the problems of people like the Hernandez’?

The Hernandez son grew up in the colonias of a city that was based on the certainty of that model. The model is still working for some: For the owners of the land and the property and for the corporations that have off-shored themselves to northern Mexico. But as an instrument of raising the economy of the society the system is broken. The “relief valve” of going to El Norte has lessened in recent years because there is less employment to be had in the U.S. The employment in the maquilas has also lessened. The employment in the private sector has gone to hell and with it the dreams of a generation.

So where does the Hernandez son go?

There aren’t a lot of options. There is one thing he can do to survive. He can be the supply for the one thing that has been flourished and been in demand in recent years in the Juarez economy: crime.

A son or daughter finding themselves in this quicksand economy can hold a gun.

If they’re desperate enough -and growing up in this war torn city is desperate- they may be ready and able to use it.

The chances of being desperate enough are high.

Mexico has done nothing about empowering the lower economic classes during most of its history. In the 19th century everything that could have turned it around didn’t. Not Pemex. Not maquilas. Not even throwing out the PRI (and then inviting it back). Nothing. One could say there have been times when they tried. The Revolution was supposed to address this with its central concern of agrarian land reform, but Mexico is no longer agrarian and the revolution failed. The real power of Mexico, even with a ten year scourge of blood and “cleansing,” did not result in the raising of the campesino. It never happened. At times it looked like it was almost happening. But like mist, the dream of a middle class, a raising of the lower income people of Mexico, dissipates, vanishes into thin air, and the same message of the centuries comes back: You’re on your own. Basically the average citizen at the bottom is left to wallow and then, if they choose, in an attempt to have some shred of dignity and well being, they can flee to El Norte where they are threatened, exploited and shunned. What an option: wallow or get yourself off-shored to the abominable and hostile norteamericano.

It should never happen to you.

But that plan doesn’t work either. You can’t off-shore everyone and a generation has grown up in sight of riches in these northern Mexico cities

Who isn’t in sight of it in this global communication world?

Where did the Cartel War begin?

It began here, in Colonia Felipe Angeles, Barrio Anapra, Juarez, Chihuahua. It began in a little casita made out of discarded truck pallets, just like the Hernandez’ but multiplied by the thousands.

Where does it end?

It doesn’t end.

At best, it quiets down.