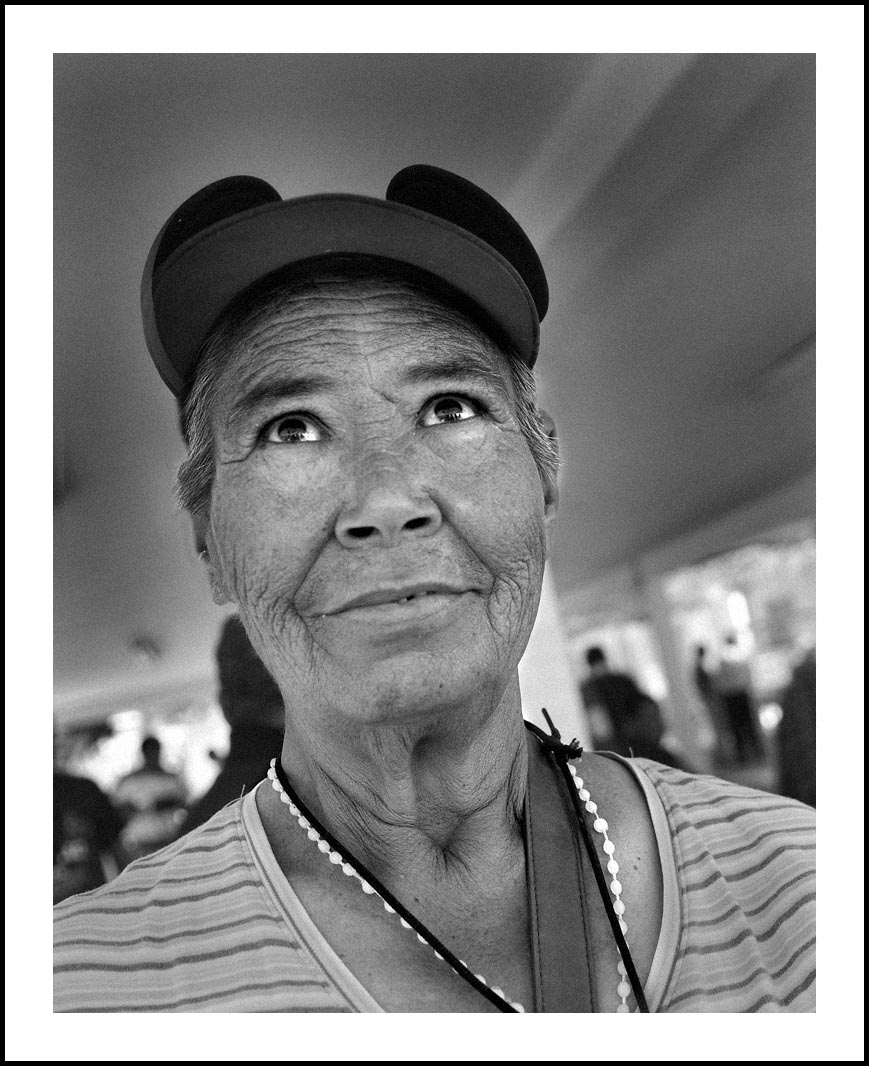

Maria Full Of Grace, from The Other Truth (T.O.T.) series,

Juárez, May 2011

Photo and Text by Bruce Berman

Juárez —

Maria. Full of grace. And other emotions.

A permanent resident of CREAMAC, in the hills of Juárez, way up there, near the Guadalupe, the last place on one of the last streets, near the top. Some people call it an “insane asylum.” It started as a place the mayor of Juárez sent “street people.”

He took an old police station and created a shelter and ordered the tourist police to “get those people off the streets.” That was 34 years ago. There are still people there…from then!

I go there, driving through the anxiety streets of the troubled city, eyes are out, sharp, both ways. These days, if you keep up with the ever terrible news coming from the Cartel War, there’s a game you play, while driving in Juárez. You match up news with the locations where it happened, that you’ve heard about: “Oh, there, that’s where the drug rehab place is: 16 murdered in three minutes. Oh…there is where the mother and son got shot. Up that street, that’s where the family got wiped out but one kid hid under the bed and survived, yeah, and over there, that’s where they put the bomb inside the guy and dressed him as a cop and called in the Cruz Roja and Policia Federal and then blew him up, right there, over by the old market.”

And so it goes.

It could go on forever on a long ride, but we race through the streets, purposely. There is no leisure in Juárez, only meaningless purposefulness.

On this day, we’re heading to the “Insane Asylum,” which seems like a more positive mission than chasing down murder scenes.

We get there and are waved in. No one asks why we want to be there or what we intend to do with our cameras and notepads. Nothing. For a journalist this seems incomprehensible, rare, curious. Where on this planet can one go into a state institution with the purpose of making pictures and a report and no one asks “why?”

The gate swings open. Dozens of people are in a yard, sprawled on the ground or sitting in the shade or milling around. The place is white on white. Everything is painted white. There is a translucent shade/roof over most of the yard. There do not seem to be guards. People immediately approach you, usually with one question: “Do you have any cigarettes?” When the answer is “no,” most wander away, back to where they had been, strangely not interested in strangers without cigarettes. There is no feeling of threat.

A few people approach you.For? For, it seems, human contact. Maria is one of those.

She tells me, lucidly, she had been a teacher. Her subjects where history, social studies, and, English. She speaks OK English. Not great. She seems very positive. I ask her about her Mickey Mouse hat. She just smiles, looks at me like, “Does that really need to be asked?” She is energetic and wants to talk. We do. People seem to want to be with her. She is like a magnet and she seems to relish the role.

I make a note to myself : “On the next visit, ‘tune in to Maria,’ she may be able to really explain this place.”

The afternoon is spent photographing, meeting people, getting as much of their story as possible, to try to understand. It is hard to understand. This doesn’t seem like an odd place (or is it that I have become “odd,” and little surprises me now?). Insane Asylum?

No, it doesn’t seem that way. Each person has a story. One is epileptic. Another is just old and tired. Another is from another city and could not find work in Juárez. There are people who speak well and there are people that can barely speak at all. Alejandro, the “Licensiado Psicología,” the psychiatric counselor, says that “…when people get too sad or too violent, we give them drugs to calm them down.” All over the place there are people laying without motion, eyes open, but not seeing. The drugs look strong.We talk. Some were abandoned as children and had been homeless. Another was “…dropped off by my Mother when I was 19,” but she won’t say why. Another says he had worked in a maquila (factory) but couldn’t keep up with it. Another says he liked to get in fights and the police “removed me.” Lots of stories, none seem to be, what most people would think of as, “insane.” People have been there for varying lengths of time but it is surprising how many say they have been there for over twenty years and, in several cases, over thirty.

This bright and exposed place, up against the mountains, in the city of the damned, doesn’t seem like an “insane asylum,” so much as it it seems like a permanent house of the abandoned. Strangely, considering the murder, kidnapping, extortion and depravity going on outside the walls, this white-on-white enterprise-less undefined place might be one of the safest places in Juárez. Behind these walls, people are safe. Safe. Where else, in Juárez, in these times, can one say that?

It turns out, there is no industry at the institution. No work to do. Three meals a day, drugs if you get too upset, but no enterprise. People mark time. Time passes slowly, but, in the end, safely.

Insane? Who would not struggle with this existence? Could I survive this? Overall, people don’t seem insane, just sad.

Indeed, on the next trip to CREAMAC, a week later, I find Maria. But it is a different Maria this time. She barely talks. She has separated from other people. She doesn’t want to talk. She cries. I come back to her, later, and ask if she is OK. She acknowledges she is feeling poorly. I ask if it is a cold or anything “serious.”

Nothing could be that simple in this strange place.

“No, I’m not sick,” she finally says, “not that way. I’m just sad for the last few days.”

I ask why.

She hesitates. Tries to formulate the words. Starts again: “My daughters don’t come anymore, the don’t visit me anymore,” she shares. She walks off. I’m taken off guard. Daughters? On the first visit she told me she had been there for 28 years. Where do they live,” I ask her. Here, in Juárez,” she manages to get out, “not far from here.” Her words do not seem to come easy. She shakes her head, stops, turns, takes a step back, starts to walk away, looks back at me, trying to focus, but her eyes not able to stop, fix on me. They seem dilated. “But,” she hesitates, stutters a bit, “it is good to see you. I hope I’m better the next time you come.”

She is still wearing the Mickey Mouse hat she wore the last time I had been here. This time it seems a bitter irony.

She pauses. Smiles a little. “Will you bring me cigarettes?” Then she walks away, going back to the privacy of her sad day.

I promise I will.

1 Comment

I am posting Maria’s photograph even though I feel our photo-interaction was private. I feel that way about all the people I have met at the House of the Abandoned. It was private. I am posting this image because the beauty of Maria, the trouble deep in that volcano, is human trouble and somehow I feel it and want others to experience it as well. I hope it’s OK.

All that is a lame way of saying I am in awe of her beauty.