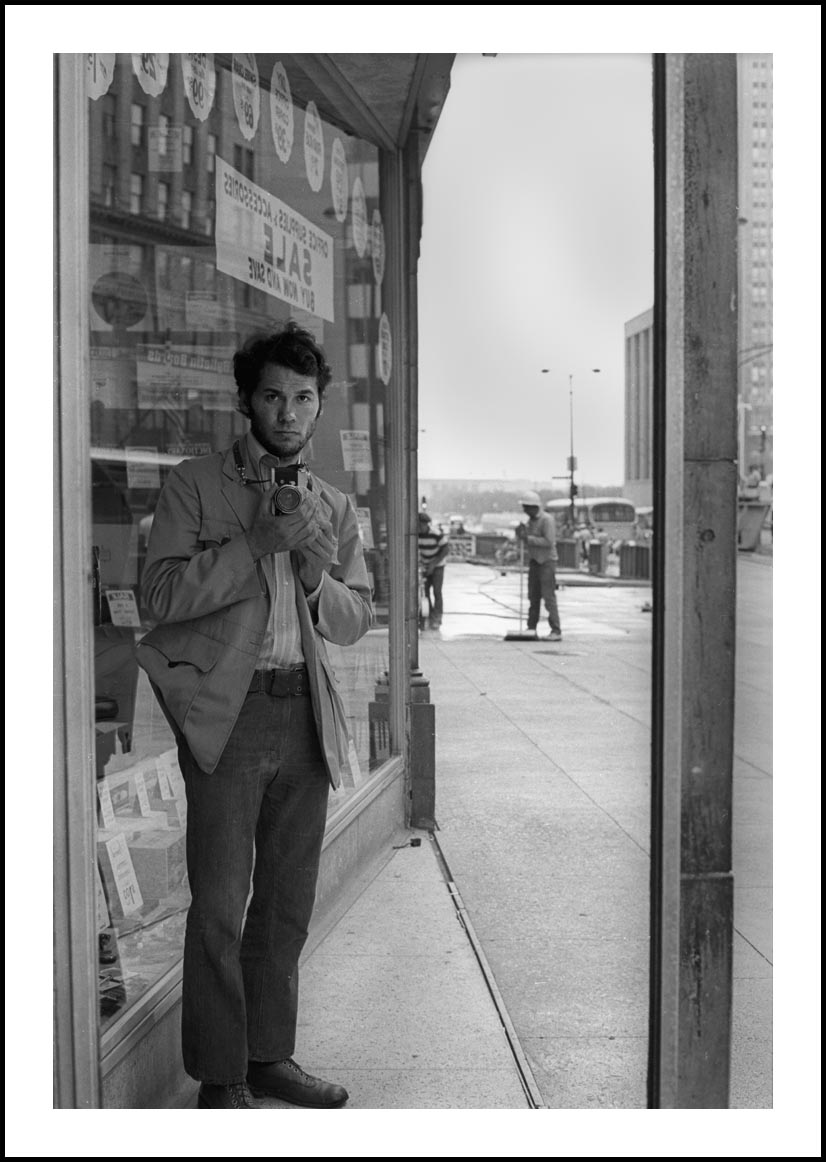

Garry Winogrand. Off kilter. Off beat. And right on in capturing the milliseconds of the oblique.

Watch this video and think about Garry lassoing the non-monumental. He was a wild puppy and full of life. Just enjoy the fun.

A memoir: Meeting Garry Winogrand

by Bruce Berman

Garry was a photographer and a winner of prizes: three Guggenheim Fellowship Awards (1964, 1969, and 1979) and a National Endowment of the Arts Award in 1979. He was a street guy and he was, most of all, a New Yorker. His photos reek “NYC.” He was hugely famous and revered in the 1970s and 80s.

I was a fan and prowled the streets of Chicago with my Canon FT QL camera, trying to see and think like he did. Eventually, it had become clear, my prowling days were going to have to come to an end. I was broke. Busted. Tapped out. Through a weird and twisted set of circumstances and connections I found a job at a “Catalog Studio” in the north suburbs. Some days I would spend the entire day arranging a 220 piece silver set, on my knees, nudging forks and spoons one way or the other, as the real photographer sat up on a ladder, looking through the back of his wooden 8 X 10 Deardorf, giving me minute instructions on their arrangement. There I became a photographer’s apprentice. This was a perfect description for the antonym of the word “glamor.” This was very “anti Winogrand.” Where he was the essence of improvisation, the job was the living- and dieing- definition of routine.

But then, one day, as fate would have it, I was sent from the blistering heat of the 12 photographer studio bay (painted completely black, photography done on hot lights, no air conditioning), through a set of white doors and I entered “heaven.” Bright white walls. Air conditioning. Everything pretty. This was the fashion photography area and it was manned by one, 5 foot 2 little guy with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth and a bevy of adoring (female) assistants and stylists hanging on his every word.

This was the guy that the boss of the sweat house studio had brought in to “save the account,” the fashion spreads of the catalogs that we did for Sears, Montgomery Ward and others.

I delivered the message that I was sent in there to deliver. We took one look at each other and the chemistry went boingo and within two days I had become the “stars” new photo assistant. I was free of the sweat mill and now on the glamor side of the biz.

The photographer’s name was Murray Laden.

He was the first photographer that I apprenticed to. He didn’t teach me everything I know but he certainly built my foundation. He’d “been there.” He’d been somewhat of a “boy wonder” in the photo district of New York, specializing in theatrical and fashion photography and he’d been a contemporary of and competitor of Avedon and Penn.

After some time we had become friendly enough -and I guess I had proved myself enough- that he asked me some questions about my ambitions in photography and what I liked.

I mentioned that I really loved the work of Garry Winogrand.

He laughed. Then he all but roared, “I taught Winogrand everything he knows.”

I was crazy about working for and learning from Murray Laden so I let this obvious unfounded boast go without challenge. Murray had a way of talking New Yorkesgue…very bombastic, bold and assertive. What the heck, I was just happy to be learning anything from a real New York photographer so, hey, let him hook on to this star (Winogrand).

I thought, surely, this must be pure hog wash.

Fast forward four years. No longer at the studio. On my own. Flopping around trying to figure out how to be a shooter.

I am in New York.

I am love struck with the city.

I had gone to almost every museum and photo show, prowled the streets looking for images. I’d finally found my way to the epicenter of photography. On the last day in the city I saw a listing for an opening reception to a new Garry Winogrand exhibition at Light Gallery on Fifth Avenue.

I was on my way to catch a bus at the Port Authority to get back to northeast Pennsylvania where I was spending a difficult summer with my girlfriend and her somewhat horrified-by-me parents. I barely had time to get myself together, let alone go uptown to a gallery and I was already 3/4s drunk (in anticipation of the three hour bus ride and arctic reception to come).

But, man! Garry Winogrand. My hero.

I made an “executive decision,” jumped on a subway and tried to get to the reception with the 50 minutes I had (almost impossible).

I had liked Winogrand’s work because it was “free,” uninhibited, rebellious. By discarding formal order for his version of order, he was the visual revolutionary that talked with me most strongly. There I was, finally, the kid from the “Second City (Chicago) in New York City and I loved it. And, as I screeched my way uptown on the E train I knew I didn’t want to leave New York City, ever. I had dreamed of being there, reveled in the stories Murray had told about his studio and getting jobs away from (Avedon (true?), about taking a young Winogrand out into the streets and showing him prefocusing of his Leica (true?) and just the entire general vibe of energy that New York exudes and that photographers need like a wounded person needs plasma.

I didn’t want to leave New York.

So, I rolled the dice, caught the train uptown and got to Light Gallery with maybe 20 minutes to spend.

I got in the elevator, got off, and pushed my way through a really packed gallery and found Mr. Winogrand. I had no time to waste so I -probably rudely- grabbed his hand, shook it and blurted out (was I slurring my words?), “Mr. Winogrand, my ex boss said if I ever met you please say hello.”

Winogrand stopped, broke off his conversation with whoever he was talking with, looked at me and asked, of course, “Who was your boss?”

Duh!

“Murray Laden,” I replied, just knowing that Winogrand had probably never heard of him before.

He squinted, then arched his eyebrows over his clear-rimmed glasses, his wild hair seemingly on alert, and bellowed, “Murray? Murray?” Then, really loudly, he yelled, “Honey,” and he reached out toward a woman standing nearby (who happened to be his wife), and shouted through the crowd, “Honey, this is a friend of Murray’s.”

He said all of this in the thickest of the thick New York accents, so that the word Murray came out something like, “Muurree.”

She smiled widely, happily, elbowed her way over to us, a beautifully pleasant and friendly smile spreading across her face, grabbed my hand and said, in a delighted voice, “Oh my gawd.”

But Winogrand had already put his arm around my shoulder, and was pulling me toward the front of the gallery.

Wow! My head was spinning for more reasons than one.

He got to where he was going, a narrow white door, put his hand on the knob and began to turn it, stopped, dropped his arm and turned to me and said, “You know, Murray taught me everything I know.” I couldn’t believe it. “Let me buy you a drink!”

He opened the door into -unbelievably- a closet, rummaged in a shoulder bag (which I presumed was his) dug out a bottle of whiskey, pouring its contents into the cups we were already holding. I got the distinct impression he had been put on a “drinking moratorium (either by the gallery or his wife)” and had stashed his bottle. He filled them to the brim, and said, really softly and believably sincerely, sweetly, lowered voice, “Here’s to Murray…I really miss him.”

It was one of the most intimate moments of my life! This, the whole New York thing, the whole crazy photography dream, all of it. My world had experienced a “9.0.”

We drank up. He talked. I needed this last shot (a triple for sure) like I needed a hole in my head.

It was a close and personal -and somewhat collegial- moment in a broom closet. It was unbelievable yet it was happening and any cynicism I had been been building up in my beginning-trying-to-make-it years dissolved like vapor, in a little closet near the front of a gallery, in mid town Manhattan, a couple of blocks from Central park, in “The City.”

We chatted a little. I was, actually, struck near-mute. He finished his drink (he was faster than I was), patted me on the shoulder and said, “Got to get back to business. I’m pushing my crap and it ain’t easy.” He looked in my eyes, smiled and said, “If ya see Murray, say ‘hiya’.”

“Stiffer” than an ironing board, I somehow got back to the Port Authority, in time, jumped on a Martz bus and headed to the Poconos and beyond, driving deep into the Pennsylvania outback, afternoon turning to deep night, half conscious, blurry, totally impressed, invigorated, in love with everything and especially, reality, and dare I say, the random order of grabbing milliseconds from the great flow of life. I was sure the life I was leading was over and that a new day had begun (which turned out true).

Or something like that.

It was as if everything I ever knew had been taught to me by these two crazy New Yorkers whose bombast turned out to be understated. For me, all else had been prelude. The beginning had begun.

When someone tells you they taught someone “everything they know,” sometimes it just might be true.

For a great read on who and what Garry Winogrand was, see: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/photo/essays/vanRiper/030131.htm

Copyright secured by Digiprove

Copyright secured by Digiprove