Man In Flames, ASARCO/El Paso – 1987

All photos ©Bruce Berman

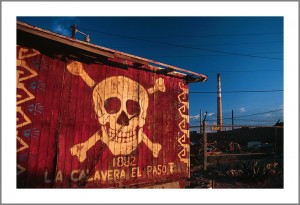

La Calavera-1986

A Dear John Letter to ASARCO

by Bruce Berman

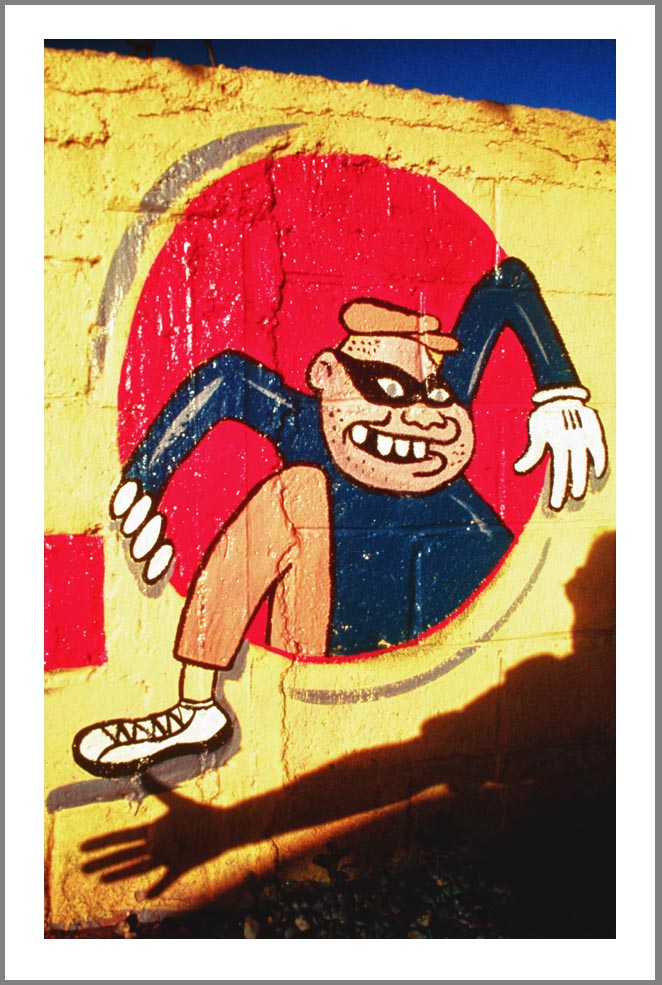

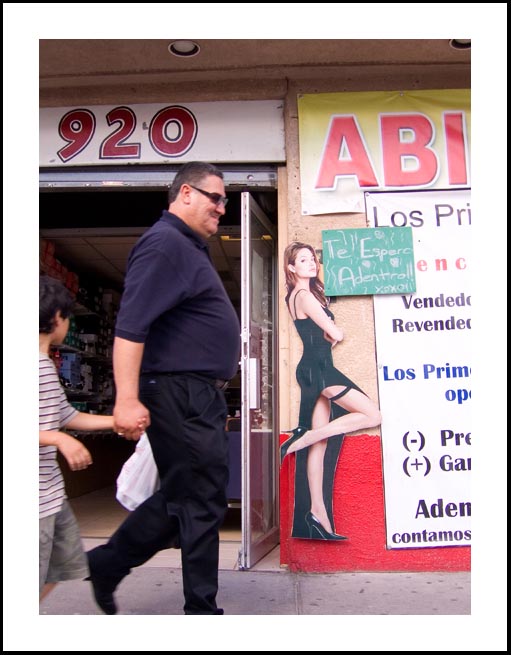

Au revoir ASARCO. You were the spine of the border, a big giant dong sticking up out of the river, pouring flames and sulfur, lead and smoke. The town grew up around you, fed off of you, then outlived you. You looked down on battles and traffic, always with the bifocals of looking at two countries at once. Looking east to El Paso, you looked down on the dusty foothills of the Franklins that became Kern Place and Mesa Hills, the sheik and elite (in its own mind). On the other, looking west, down into the dust and turbulence of Juarez, you looked down onto Colonia Felipe Angeles, which, too was foothills, that became a shanty town which became a barrio which became (shhhh..not quite yet) a path to a port of entry into New Mexico. What a vantage point you have had. When I first saw you I stood up straight, saluted and said, Wow, yes sir!

I dug you from the gitgo, had the pleasure of working inside you, being constantly re-awakened by you, of working inside you near those flames with the weather outside 105 degrees, feeling the comradie of your workers, the satisfaction of being inside something that wild and crazy and productive, a caldron of energy and raw power.

You were one of the main reasons I could stay in this aimless city, you were my south side of Chicago all over again, home, and you kept me cranked up for 40 years.

You acted as a landmark, externally and internally.

You’re all but gone now. Building by building, furnace by furnace, the holding lake, showers, Brine Concentrator, gone. Your flames and puckering sulfur and deep sweat, gone. Your utter machismo, gone. People will drive by you on I10 and the historians will relate your past, they’ll recount the litany of the battle of the revolution, tales of the wild river, talk of little Madero and his camp. But it’s all gone now. One will cruise through, and note how fierce you were.

Fierce? Dude, you were the balls!

There is a movement to save your great grand smokestack. La chimenea. The phallic flag of a town that was always softer than it thought it was

I say blow it down.

Victors shouldn’t stuff the game trophy.

You were for the living. You were for the working. You were for the building. Your smokestack was like an ear is to a person: just a digit. Nope, blow it down and move on. It’s been coming for decades. Your chignon-ness isn’t for a museum. It was for living wild and free.

I photographed you. I photographed you a lot. I worked with my friend Paul Salopek on the Mexicano side on Sobre La Chimenea (which became Dust and Dreams)and came to know the Macias family (a gift, a lifetime of lessons in one summer). I worked inside of you and put on the blue jump suit for a year and wandered free making pictures of the men who made the place’s heart tick. I climbed your scaffolds with my friend Kerry and we made art out of your control room. I came back later and made shiny pictures of your aluminum-skinned water-scrubbing Brine Concentrator. I stood in the dust below you with Esther Chavez Cano and tried to rescue two young girls. ON 9/11 I was “detained” underneath you by railroad detectives wondering if I was a terrorist planning another strike. I came back to you many many evenings, just you and I, and I worked with you and the light and with me, talking to myself a lot as you listened with your steady whisper of smoke and steam. I worked with you to become me.

I won’t photograph you anymore. You’re dead now. I for sure won’t photograph your destruction. I draw the line at autopsies. The last element of you, the smokestack, La Chimenea, a mummy, stands, for now, but it’s bad luck to voluntarily photograph the dead (something I have been forced into in recent years on your west bank).

How do you put a camera around what was, around nothing?

Answer: you don’t.

One finds somewhere else and something else to wrap that tool around and one doesn’t look back.

The nature of photography, at least as I’ve known it, is to find something on the lens-side to love and to share it, and, if possible, startle those you hand it to.

No, now I need to bury you, say my little prayers, toss some dust at you and ride away. That’s what one does at the end, no?

Truth is, in the last few years I stopped loving you and have just enjoyed the memory. I’ve already moved on. I drive back and forth past you, several times every week for the past six years, on my way to my new hunting ground, to New Mexico (where I’ve almost talked myself to death). You became more gray and lifeless, as time has passed, a bad sign on anyone, a thing no longer really among us. For pure plasma, sometimes, I’d go to Juarez, dropping the color photography and the seeking of graphics (and somewhere along the line dropped the joy too) and just settled down into working with murder and mental illness, working, another death in the making. Yours.

I never loved you, or Juarez or El Paso for what it could become.

I loved -and hated- you for what you were:Big and nasty and vulnerable all at the same time.

There won’t be much more to do, here, for me, now. You can’t put your camera around nothing.

So, I kiss your hissing sulfur lips goodbye. We were good for each other, no?

Luego.