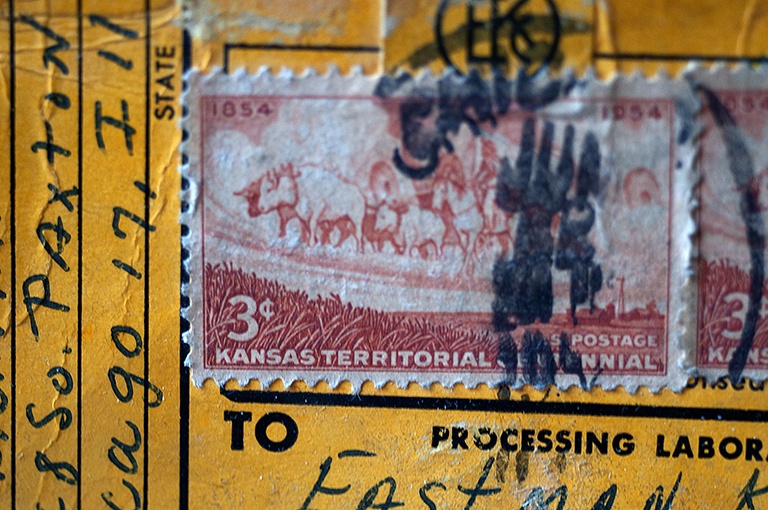

Cancellation #93, Mom’s Kodak film, Chicago, 1950s

I once did an entire series of photographs called “Cancellations.”

It started because one day I was looking at a stack of shipping boxes of my photographs that I had sent to various galleries and museums (pre Internet) that had been summarily rejected. Thanks. No thanks, return to sender. There were a lot of stamps on those heavy boxes. The post office cancellations were ruthless, slashing, colorful. It’s like the post office knew I was unworthy, as well. I half jokingly wondered if the galleries hadn’t done it themselves.

I got lucky here and there, exhibited them for awhile. Dallas. Houston. Cologne, Germany. The art world thought they had found a new star. I knew I was a fraud.

People who knew me were going “What in the hell are you doing!????”

I thought it was clever. Get it. Making success out of rejection. You know. The great American story. Isn’t art all about being clever? Problem is, I’ve never been that clever and when I try to be I’ve usually exposed my own deep seated fears that I’m not too smart (or clever)!

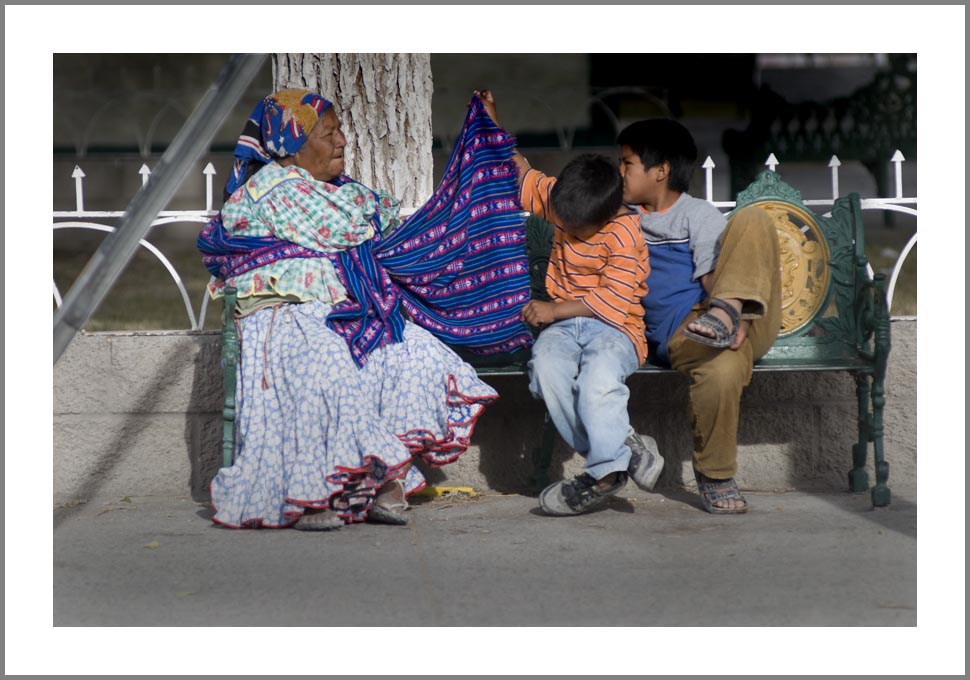

Within a year, even with the little run of success I was having, I quit doing those photos. It really wasn’t me. Soon thereafter I realized there was no place in the world of Art for me, at all. When I got my first real camera I headed out to the complete unglamorous west side, shooting in the back alleys of Chicago and have ended up shooting deep in the barrios of El Paso and Juárez.

I did not head to the art museum and galleries on Michigan Avenue.

Information, I realized, is what I was after. Human connection. The bizarre, The notable. Anything that allowed me to connect to humanity.

Shooting exquisitely composed and beautifully lit cancelled stamps somehow just didn’t fit that need and desire.

The other day I came across a returned small parcel/box, about 4″ X 3″. It had originally come with. Inside of it was a 25 foot roll of 8mm movie film, processed by Kodak. It had my mother’s handwriting on it. I looked again. The return address was my boyhood home and there was no zip code. It was, clearly, pre Zip Code. And, of course, it was a Kodak yellow, which is synonymous with the word PHOTOGRAPHY itself. Kodak film. Kodak cameras. Kodak processing. Everything was Kodak in the 1950s (and, really, for the prior 70 years, when George Eastman invented the Brownie, and all people would become photographers). Kodak, to me meant excitement and innovation and, I don’t know, somehow, even then, a personal destination.

And, if you look again it’s stamp was a centennial commemoration stamp about Kansas. The box was probably mailed in 1954. I was 10.

That box is a world of information.

It held my memories. Memories of my Mom, of here playing cowboys and Indians with me (‘d say, I’m the cowboy, you’re the “cow mom.” She’d laugh and always delighted in telling that to others!), our annual trip to the flower market for Spring planting, memories of my Dad, holed up in his home office -no one had a home office in the 1950s- his six telephones, sometimes ringing at once, always talking about sports, I really didn’t know what he did for a living, but, you can do the math, always running on adrenalin, hoping the odds (literally) were with him that day, of my sister in her teen rebellion years, doing everything she could to defy the norms.

So when I came on this box the other day, the address on the box cracked my memory banks wide open and I remembered the house I grew up in on the south side -I miss it still- adventures with my best buddy Jimmy Lowery from across the street, us running wild and free up and down the nearby Lake Michigan shore. The yellow box was a box with film of my family, pre-breakup, of the good times of childhood of knowing nothing and thus innocence. There was only happiness in that old box.

It was more than a box. I knew it. It’s true.

So, I thought, these six decades later, being a photographer -a documentary photographer-now, after such a long time, the box was worthy of a photograph, a photograph of a treasure, a memory box.

I was creating a new memory with a new photograph of my family’s old ancient heart.

What is photography if not a memory machine?

The act of shooting it was a pleasure, an act of uncancelling, long gone memories closed off for decades, opened up again.

The photograph was an uncancellation, a document stretched across seven decades.

Feels good.