Drug cartels want migrants’ routes

Fight to control corridors on Arizona border turns violent

ALTAR, Mexico ˆ This village on the edge of the Sonoran Desert has been a supermarket for smugglers and the smuggled for nearly a decade. Migrants choose from an array of packages offered by coyotes and pick up day packs and anti-dehydration potions for the trek north.

Now drug smugglers want their route. And to drive home their point, they’ve burned nearly two dozen vehicles of van drivers in the last two months, and left migrants shoeless in the sands of the Sonora.

The violence spilled into Arizona last week: Three Guatemalans in a truck carrying illegal immigrants were killed in a shooting northwest of Tucson.

Some officials say human smugglers are fighting among themselves and ripping off migrant customers.

But others point to reputed drug-cartel leader Joaquin “Chapo” Guzman ˆ whose nickname is Spanish slang for “Shorty.”

Mr. Guzman is the reputed leader of the drug cartel named for his Mexican home state of Sinaloa. And he wants the Sonoran route in the same way that Mexico’s Zeta gang wants Interstate 35 from Laredo through Texas, said two law enforcement officials in the U.S.

“Chapo’s ambition is nothing short of taking control of the Mexican border,” said one U.S. law enforcement official who’s been on Mr. Guzman’s trail for nearly a decade and agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity. “He’s a crafty drug trafficker and ruthless killer who also happens to be a brilliant businessman. And there’s nothing more lucrative on the border than control of vital transit border routes. You mess with his routes and often you pay the ultimate price.”

Human smuggling is a lucrative business, with fees tripling in recent years and as many as nine out of 10 illegal immigrants using a smuggler to get into the U.S.

‘Guzman’s territory’

Chapo Guzman covets I-35, as well, and that’s inspired a running soundtrack of violence at the Texas border.

DAMEON RUNNELS/DMN Staff Artist

“This is Chapo Guzman’s territory,” says Gustavo Soto, a Border Patrol spokesman for the Tucson sector, the nation’s most heavily trafficked.

In Altar last week, many immigrants at the central plaza and those working at a shelter were buzzing about the violence.

“They’re actually burning buses now,” says Marcos Burruel, a volunteer at a migrant shelter in Altar. “These guys are trying to control the corridor for drugs, and they don’t want migrants using it. … And all we can do is give warnings.”

Isaac Catalan would love a job in construction in the Carolinas, he says. But the Arizona border is now “tapado por la mafia,” closed by the mafia, says Mr. Catalan, who tried to cross three times and lost more than $3,000 in the attempts.

“There’s too much vigilance, too much,” says Mr. Catalan, who comes from Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas. “And it’s not the Border Patrol.”

Fernando MartÃnez nods in agreement. His brother was knifed in the leg and robbed of $600 when he tried to cross the border near Sásabe, a popular crossing west of Nogales, he says.

“We want President Bush to know what’s happening here,” Mr. Martinez says.

And then Andrés Murrieta, a plaza taco vendor in a big blue apron, jumps in. Migrants died in a gunbattle ˆ after they crossed into Arizona, he says.

Too much violence

Drivers in battered vans complain that business is off 20 percent to 50 percent because of the drug violence.

They charge $10 a head to take people to Sásabe, Mexico. But they won’t go near El Chango, just west of Sásabe. That’s too violent, they say.

“I won’t take you to Chango,” says Angel Monreal, a beefy driver. “I just drive to Sásabe.”

At the plaza, the steeple on the church of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe juts into the sky defiantly. It’s encircled by desperation. For $3 a night, casas de huespuedes, guest houses, beckon migrants to rest.

Fliers from human rights organizations here warn that trabajo forzado , forced labor, is illegal.

Inside the church, there are more fliers ˆ images of Roselia Romero Ruiz and Simitrio Santiago. They’ve disappeared.

Arizona is the heaviest sector for the U.S. Border Patrol for illegal immigrants. Nearly half of the arrests happen here, and it’s been targeted for a test of the newest technology for the year-old Secure Border Initiative.

That shift in traffic to Arizona took place as the Border Patrol tried to place tourniquets in Texas and California on the migrant flow in the mid-1990s. Then came even more enforcement after the 2001 terrorist attacks on the East Coast.

Three years ago, Mexico began cracking down on top drug cartels, from Tijuana to Matamoros, freeing some routes and forcing a war among cartel leaders for more territory. As the cartels fight for plazas, slang for crucial real estate to bring drugs into the U.S., the violence has shot up.

On the Texas border, Nuevo Laredo, a busy commercial port, is one of the most violent cities on an already violent border. But migrant traffic through Laredo is only a fifth of what is in the Tucson-Nogales region, according to Border Patrol statistics of apprehensions.

Chris Simcox of the Arizona-based Minutemen Civil Defense Corps, an anti-illegal immigration group that patrols the border, says violence is so bad that even those on his patrols are getting nervous. “We are certainly on edge out there now, too,” Mr. Simcox says. “We don’t want to encounter any of those vicious gangs.

“The drug smugglers are emboldened to do whatever they want,” Mr. Simcox says. “And we have a moral obligation to stop this.”

Adds Evelyn H. Cruz, a law professor at Arizona State University, “We are creating the Al Capones of the 21st century.”

Problems grow

With an increase in the number of migrants who turn to smugglers, migration experts say, the problems will only escalate.

An analysis by the Associated Press of 60,000 illegal immigrants surveyed over six years found that half were using smugglers by mid-2005, up from about a fifth in 2003. The College of the Northern Border in Baja California conducted the surveys.

In a separate study of about 1,300 immigrants and their families at the University of California at San Diego, researchers found that nine out of 10 used smugglers.

And high season in the Sonora is starting.

That’s when the flow of border crossers really picks up, says DarÃo GarcÃa of Grupo Beta, an organization that assists migrants from any country and Mexican deportees.

Nogales becomes a Babel on the border, Mr. GarcÃa said. They come from Russia, Poland, Brazil, China and India, he said. All ages.

But the children worry him most, he said.

“One time, I found a girl who was 9 years old and had been raped in front of her mother,” he says. “Her mother was 6 months pregnant and was raped, too.”

Still, the migrants and their smugglers come up with new ways to cross ˆ despite increasing technological barriers ˆ using their own GPS gadgets and even an impostor Border Patrol van with the green insignia. They’ve used metal detectors to pull sensors from their hiding places. And if they spot a wayward antenna, they’ve been known to simply urinate on it, officials say. Like a keyboard doused by coffee, the sensor is rendered senseless.

“It’s a very difficult job,” says the Border Patrol’s Mr. Soto, who carries a .40-caliber Beretta handgun in his holster. “They shoot at us. They throw rocks at us and they even try to ram us with vehicles.”

Drug cartels want migrants’ routes

Fight to control corridors on Arizona border turns violent

ALTAR, Mexico ˆ This village on the edge of the Sonoran Desert has been a supermarket for smugglers and the smuggled for nearly a decade. Migrants choose from an array of packages offered by coyotes and pick up day packs and anti-dehydration potions for the trek north.

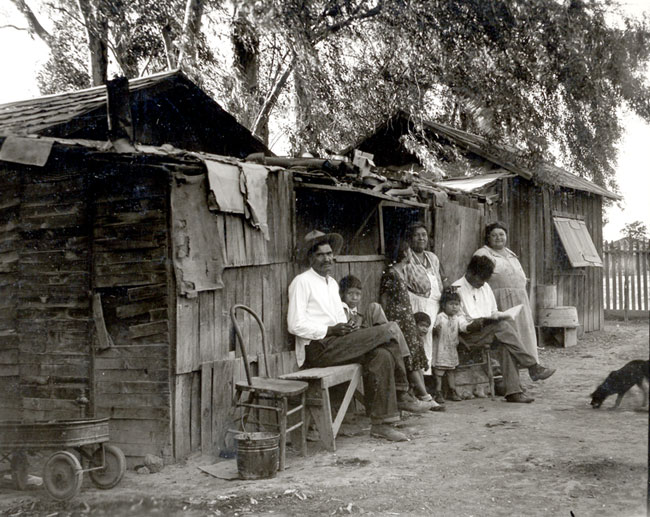

AP

Joe Romero of Wackenhut Transportation processes a suspected illegal immigrant in the Tucson sector near the Arizona-Mexico border. The U.S. Border Patrol sees heavy traffic from illegal immigrants in Arizona.

Now drug smugglers want their route. And to drive home their point, they’ve burned nearly two dozen vehicles of van drivers in the last two months, and left migrants shoeless in the sands of the Sonora.

The violence spilled into Arizona last week: Three Guatemalans in a truck carrying illegal immigrants were killed in a shooting northwest of Tucson.

Some officials say human smugglers are fighting among themselves and ripping off migrant customers.

But others point to reputed drug-cartel leader Joaquin “Chapo” Guzman ˆ whose nickname is Spanish slang for “Shorty.”

Mr. Guzman is the reputed leader of the drug cartel named for his Mexican home state of Sinaloa. And he wants the Sonoran route in the same way that Mexico’s Zeta gang wants Interstate 35 from Laredo through Texas, said two law enforcement officials in the U.S.

“Chapo’s ambition is nothing short of taking control of the Mexican border,” said one U.S. law enforcement official who’s been on Mr. Guzman’s trail for nearly a decade and agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity. “He’s a crafty drug trafficker and ruthless killer who also happens to be a brilliant businessman. And there’s nothing more lucrative on the border than control of vital transit border routes. You mess with his routes and often you pay the ultimate price.”

Human smuggling is a lucrative business, with fees tripling in recent years and as many as nine out of 10 illegal immigrants using a smuggler to get into the U.S.

‘Guzman’s territory’

Chapo Guzman covets I-35, as well, and that’s inspired a running soundtrack of violence at the Texas border.

DAMEON RUNNELS/DMN Staff Artist

“This is Chapo Guzman’s territory,” says Gustavo Soto, a Border Patrol spokesman for the Tucson sector, the nation’s most heavily trafficked.

In Altar last week, many immigrants at the central plaza and those working at a shelter were buzzing about the violence.

“They’re actually burning buses now,” says Marcos Burruel, a volunteer at a migrant shelter in Altar. “These guys are trying to control the corridor for drugs, and they don’t want migrants using it. … And all we can do is give warnings.”

Isaac Catalan would love a job in construction in the Carolinas, he says. But the Arizona border is now “tapado por la mafia,” closed by the mafia, says Mr. Catalan, who tried to cross three times and lost more than $3,000 in the attempts.

“There’s too much vigilance, too much,” says Mr. Catalan, who comes from Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas. “And it’s not the Border Patrol.”

Fernando MartÃnez nods in agreement. His brother was knifed in the leg and robbed of $600 when he tried to cross the border near Sásabe, a popular crossing west of Nogales, he says.

“We want President Bush to know what’s happening here,” Mr. Martinez says.

And then Andrés Murrieta, a plaza taco vendor in a big blue apron, jumps in. Migrants died in a gunbattle ˆ after they crossed into Arizona, he says.

Too much violence

Drivers in battered vans complain that business is off 20 percent to 50 percent because of the drug violence.

They charge $10 a head to take people to Sásabe, Mexico. But they won’t go near El Chango, just west of Sásabe. That’s too violent, they say.

“I won’t take you to Chango,” says Angel Monreal, a beefy driver. “I just drive to Sásabe.”

At the plaza, the steeple on the church of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe juts into the sky defiantly. It’s encircled by desperation. For $3 a night, casas de huespuedes, guest houses, beckon migrants to rest.

Fliers from human rights organizations here warn that trabajo forzado , forced labor, is illegal.

Inside the church, there are more fliers ˆ images of Roselia Romero Ruiz and Simitrio Santiago. They’ve disappeared.

Arizona is the heaviest sector for the U.S. Border Patrol for illegal immigrants. Nearly half of the arrests happen here, and it’s been targeted for a test of the newest technology for the year-old Secure Border Initiative.

That shift in traffic to Arizona took place as the Border Patrol tried to place tourniquets in Texas and California on the migrant flow in the mid-1990s. Then came even more enforcement after the 2001 terrorist attacks on the East Coast.

Three years ago, Mexico began cracking down on top drug cartels, from Tijuana to Matamoros, freeing some routes and forcing a war among cartel leaders for more territory. As the cartels fight for plazas, slang for crucial real estate to bring drugs into the U.S., the violence has shot up.

On the Texas border, Nuevo Laredo, a busy commercial port, is one of the most violent cities on an already violent border. But migrant traffic through Laredo is only a fifth of what is in the Tucson-Nogales region, according to Border Patrol statistics of apprehensions.

Chris Simcox of the Arizona-based Minutemen Civil Defense Corps, an anti-illegal immigration group that patrols the border, says violence is so bad that even those on his patrols are getting nervous. “We are certainly on edge out there now, too,” Mr. Simcox says. “We don’t want to encounter any of those vicious gangs.

“The drug smugglers are emboldened to do whatever they want,” Mr. Simcox says. “And we have a moral obligation to stop this.”

Adds Evelyn H. Cruz, a law professor at Arizona State University, “We are creating the Al Capones of the 21st century.”

Problems grow

With an increase in the number of migrants who turn to smugglers, migration experts say, the problems will only escalate.

An analysis by the Associated Press of 60,000 illegal immigrants surveyed over six years found that half were using smugglers by mid-2005, up from about a fifth in 2003. The College of the Northern Border in Baja California conducted the surveys.

In a separate study of about 1,300 immigrants and their families at the University of California at San Diego, researchers found that nine out of 10 used smugglers.

And high season in the Sonora is starting.

That’s when the flow of border crossers really picks up, says DarÃo GarcÃa of Grupo Beta, an organization that assists migrants from any country and Mexican deportees.

Nogales becomes a Babel on the border, Mr. GarcÃa said. They come from Russia, Poland, Brazil, China and India, he said. All ages.

But the children worry him most, he said.

“One time, I found a girl who was 9 years old and had been raped in front of her mother,” he says. “Her mother was 6 months pregnant and was raped, too.”

Still, the migrants and their smugglers come up with new ways to cross ˆ despite increasing technological barriers ˆ using their own GPS gadgets and even an impostor Border Patrol van with the green insignia. They’ve used metal detectors to pull sensors from their hiding places. And if they spot a wayward antenna, they’ve been known to simply urinate on it, officials say. Like a keyboard doused by coffee, the sensor is rendered senseless.

“It’s a very difficult job,” says the Border Patrol’s Mr. Soto, who carries a .40-caliber Beretta handgun in his holster. “They shoot at us. They throw rocks at us and they even try to ram us with vehicles.”